-

Writing a paragraph

-

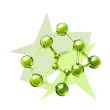

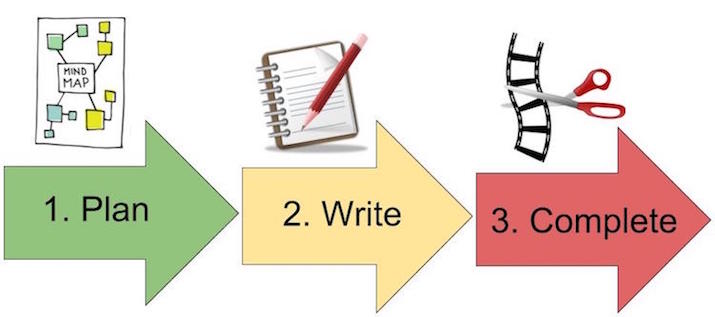

The writing process

-

|

Infographic

https://study.com/academy/lesson/practical-application-three-step-writing-process-infographic.html

Behind each writing project lies the purpose, for its being undertaken. Purposes for writing vary, and each makes its own demands on the writer. Here some typical purposes for writing:

-

To narrate something about your life or ideas that’s worth knowing

-

To give information

-

To analyze a text

-

To argue or persuade

*In favor of a point of view on a debatable issue

*In favor of a proposal or a solution to a problem

-

To evaluate the quality of a text, object, individual, or event

The audience for your writing can consist of different people. Imagining who your readers are increases chances for engaging their attention. Ways to imagine your audience:

-

Their level of knowledge

-

Their interests

-

Their beliefs

-

Their backgrounds

-

Relation to you

Brainstorming means listing everything that comes to mind about your topic. Let your mind room, and jot down all ideas that flow logically or that simply pop into your head. After you have brainstormed for a while, look over your list for patterns. If you don’t have enough to work with, choose one item in your list and brainstorm from there.

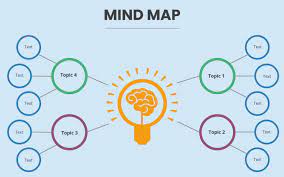

Mapping is a visual form of brainstorming. Write your topic in the middle and then circle it. Move out from the middle circle by drawing lines with circles at the end of each line. Put in each circle a subtopic related to the main topic.

https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.mindmapper.com%2Fbenefits-of-mind

EXERCISE 1

Here is a list of brainstormed items. Organize them in a mind map. The topic is “Ways to promote a new movie”.

Previews in theaters suspense director

TV ads book the movie was based on topical subject

Provocative locations special effects

Movie reviews internet trailers dialogue

How movie was made adventure excitement

Sneak previews newspaper ads photography

Word of mouth stars Facebook page

-

Outlining

An outline is a structured, sequential list of the contents of a text. An informal outline does not follow the numbering and lettering conventions of a formal outline. It often looks like a brainstorming list, with ideas jotted down in a somewhat random order.

A formal outline follows long – established conventions for using numbers and letters to show relationships among ideas. To compose a formal outline, always use at least two subdivisions at each level – no I without a II, no A without a B. If a level has only one subdivision, either integrate it into the higher level or expand it into two subdivisions.

Thesis statement/topic sentence

-

First main idea

-

First subordinate idea

-

First reason or example

-

Second reason or example

-

First supporting detail

-

Second supporting detail

-

Second subordinate idea

-

Second main idea

-

Paragraph

A paragraph is a group of sentence that work together to develop a unit of thoughts. Paragraphs help you divide material into manageable parts and arrange the parts in a unified whole. Academic writing typically consists of an introductory paragraph, a group of body paragraphs, and a concluding paragraph.

Introductory paragraphs point to what lies ahead and seek to arouse readers’ interest.

-

Provide relevant background information about your topic.

-

Relate a brief.

-

Give pertinent, perhaps surprising statistics about your topic.

-

Ask a provocative question to lead into your topic.

-

Use a quotation that relates closely to your topic.

-

Draw an analogy to clarify or illustrate your topic.

-

Define a key term you use throughout your piece of writing.

A topic sentence contains the main idea of a body paragraph and controls its content. Topic sentences are usually generalizations containing the main idea of the paragraph. The connection between the main idea and its supporting details in the sentences that follow it needs to be clear. Topic sentences usually come at the beginning of a paragraph, but putting them at the end or implying them can be effective in some cases. When a topic sentence starts a paragraph, readers immediately know what topic will be discussed. When a topic sentence ends a body paragraph, all sentences leading to it need to flow into it clearly. Some paragraphs convey a main idea without a specific topic sentence. This technique requires special care so that the details clearly add up to a main idea.

EXERCISE 2

Working individually or with a group, identify the topic sentences in the following paragraphs. If the topic sentence is implied, write the point the paragraph conveys.

-

Nothing can dampen the excited anticipation of camping more than a dark, rainy day. Even the most adventurous campers can lose some of their enthusiasm on the drive to the campsite if the skies are dreary and damp. After reaching their destination, campers must then "set up camp" in the downpour. This includes keeping the inside of the tent dry and free from mud, getting the sleeping bags situated dryly, and protecting food from the downpour. If the sleeping bags happen to get wet, the cold also becomes a major factor. A sleeping bag usually provides warmth on a camping trip; a wet sleeping bag provides none. Combining wind with rain can cause frigid temperatures, causing any outside activities to be delayed. Even inside the tent problems may arise due to heavy winds. More than a few campers have had their tents blown down because of the wind, which once again begins the frustrating task of "setting up camp" in the downpour. It is wise to check the weather forecast before embarking on camping trips; however, mother nature is often unpredictable and there is no guarantee bad weather will be eluded.

-

Another problem likely to be faced during a camping trip is run-ins with wildlife, which can range from mildly annoying to dangerous. Minor inconveniences include mosquitoes and ants. The swarming of mosquitoes can literally drive annoyed campers indoors. If an effective repellant is not used, the camper can spend an interminable night scratching, which will only worsen the itch. Ants do not usually attack campers, but keeping them out of the food can be quite an inconvenience. Extreme care must be taken not to leave food out before or after meals. If food is stored inside the tent, the tent must never be left open. In addition to swarming the food, ants inside a tent can crawl into sleeping bags and clothing. Although these insects cause minor discomfort, some wildlife encounters are potentially dangerous. There are many poisonous snakes in the United States, such as the water moccasin and the diamond-back rattlesnake. When hiking in the woods, the camper must be careful where he steps. Also, the tent must never be left open. Snakes, searching for either shade from the sun or shelter from the rain, can enter a tent. An encounter between an unwary camper and a surprised snake can prove to be fatal. Run-ins can range from unpleasant to dangerous, but the camper must realize that they are sometimes inevitable.

-

Perhaps the least serious camping troubles are equipment failures; these troubles often plague families camping for the first time. They arrive at the campsite at night and haphazardly set up their nine-person tent. They then settle down for a peaceful night's rest. Sometime during the night the family is awakened by a huge crash. The tent has fallen down. Sleepily, they awake and proceed to set up the tent in the rain. In the morning, everyone emerges from the tent, except for two. Their sleeping bag zippers have gotten caught. Finally, after fifteen minutes of struggling, they free themselves, only to realize another problem. Each family member's sleeping bag has been touching the sides of the tent. A tent is only waterproof if the sides are not touched. The sleeping bags and clothing are all drenched. Totally disillusioned with the "vacation," the frustrated family packs up immediately and drives home. Equipment failures may not seem very serious, but after campers encounter bad weather and annoying pests or wild animals, these failures can end any remaining hope for a peaceful vacation.

https://www.jscc.edu/academics/programs/writing-center/writing-resources/five-paragraph- essay.html

Body paragraphs in an essay come after the introductory paragraph. The sentences support the generalization in the topic sentence. If you need help in thinking of details, try using RENNS.

R = Reasons can provide support.

E = Examples can provide support.

N = Names can provide support.

N = Numbers can provide support.

S = Senses – sight, sound, smell, taste, touch – provide support.

The concluding paragraph of an essay needs to follow logically from your thesis statement and body paragraphs. Never merely tack on a conclusion. Your concluding paragraph provides a sense of completion, a finishing touch that enhances the whole essay.

-

Paragraph coherence

A paragraph has coherence when its sentences are connected in content and relate to each other in form and language. Coherence creates a smooth flow of thoughts within each paragraph as well as from one paragraph to another. Transitional words and expressions, deliberate repetition, and parallelism can help make your writing coherent.

Transitional expressions are words and phrases that express connections among ideas, both within and between paragraphs. Here are some tips for using transitions effectively.

-

Vary the transitional expressions that you use within a category.

-

Use each transitional expression precisely, according to its exact meaning.

|

ADDITION – also, besides, equally important, furthermore, in addition, moreover, too COMPARISON – in the same way, likewise, similarly CONCESSION – granted, naturally, of course CONTRAST – at the same time, certainly, despite the fact that, however, in contrast, instead, nevertheless, on the contrary, on the other hand, otherwise, still EMPHASIS – indeed, in fact, of course EXAMPLE – a case in point, as an illustration, for example, for instance, namely, specifically PLACE – here, in the background, in the front, nearby, there RESULT – accordingly, as a result, consequently, hence, then, therefore, thus SUMMARY – finally, in conclusion, in short, in summary TIME SEQUENCE – eventually, finally, meanwhile, next, now, once, then, today, tomorrow, subsequently, yesterday |

-

Academic writing from paragraph to essay. Dorothy E Zemach, Lisa A Rumisek. Macmillan , 2015

-

Quick access, reference for writers, 7th edition. Lynn Q. Troyka, Douglas Hesse. Pearson, 2013

жүктеу мүмкіндігіне ие боласыз

Бұл материал сайт қолданушысы жариялаған. Материалдың ішінде жазылған барлық ақпаратқа жауапкершілікті жариялаған қолданушы жауап береді. Ұстаз тілегі тек ақпаратты таратуға қолдау көрсетеді. Егер материал сіздің авторлық құқығыңызды бұзған болса немесе басқа да себептермен сайттан өшіру керек деп ойласаңыз осында жазыңыз

Paragraph writing basics

Paragraph writing basics

-

Writing a paragraph

-

The writing process

-

|

Infographic

https://study.com/academy/lesson/practical-application-three-step-writing-process-infographic.html

Behind each writing project lies the purpose, for its being undertaken. Purposes for writing vary, and each makes its own demands on the writer. Here some typical purposes for writing:

-

To narrate something about your life or ideas that’s worth knowing

-

To give information

-

To analyze a text

-

To argue or persuade

*In favor of a point of view on a debatable issue

*In favor of a proposal or a solution to a problem

-

To evaluate the quality of a text, object, individual, or event

The audience for your writing can consist of different people. Imagining who your readers are increases chances for engaging their attention. Ways to imagine your audience:

-

Their level of knowledge

-

Their interests

-

Their beliefs

-

Their backgrounds

-

Relation to you

Brainstorming means listing everything that comes to mind about your topic. Let your mind room, and jot down all ideas that flow logically or that simply pop into your head. After you have brainstormed for a while, look over your list for patterns. If you don’t have enough to work with, choose one item in your list and brainstorm from there.

Mapping is a visual form of brainstorming. Write your topic in the middle and then circle it. Move out from the middle circle by drawing lines with circles at the end of each line. Put in each circle a subtopic related to the main topic.

https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.mindmapper.com%2Fbenefits-of-mind

EXERCISE 1

Here is a list of brainstormed items. Organize them in a mind map. The topic is “Ways to promote a new movie”.

Previews in theaters suspense director

TV ads book the movie was based on topical subject

Provocative locations special effects

Movie reviews internet trailers dialogue

How movie was made adventure excitement

Sneak previews newspaper ads photography

Word of mouth stars Facebook page

-

Outlining

An outline is a structured, sequential list of the contents of a text. An informal outline does not follow the numbering and lettering conventions of a formal outline. It often looks like a brainstorming list, with ideas jotted down in a somewhat random order.

A formal outline follows long – established conventions for using numbers and letters to show relationships among ideas. To compose a formal outline, always use at least two subdivisions at each level – no I without a II, no A without a B. If a level has only one subdivision, either integrate it into the higher level or expand it into two subdivisions.

Thesis statement/topic sentence

-

First main idea

-

First subordinate idea

-

First reason or example

-

Second reason or example

-

First supporting detail

-

Second supporting detail

-

Second subordinate idea

-

Second main idea

-

Paragraph

A paragraph is a group of sentence that work together to develop a unit of thoughts. Paragraphs help you divide material into manageable parts and arrange the parts in a unified whole. Academic writing typically consists of an introductory paragraph, a group of body paragraphs, and a concluding paragraph.

Introductory paragraphs point to what lies ahead and seek to arouse readers’ interest.

-

Provide relevant background information about your topic.

-

Relate a brief.

-

Give pertinent, perhaps surprising statistics about your topic.

-

Ask a provocative question to lead into your topic.

-

Use a quotation that relates closely to your topic.

-

Draw an analogy to clarify or illustrate your topic.

-

Define a key term you use throughout your piece of writing.

A topic sentence contains the main idea of a body paragraph and controls its content. Topic sentences are usually generalizations containing the main idea of the paragraph. The connection between the main idea and its supporting details in the sentences that follow it needs to be clear. Topic sentences usually come at the beginning of a paragraph, but putting them at the end or implying them can be effective in some cases. When a topic sentence starts a paragraph, readers immediately know what topic will be discussed. When a topic sentence ends a body paragraph, all sentences leading to it need to flow into it clearly. Some paragraphs convey a main idea without a specific topic sentence. This technique requires special care so that the details clearly add up to a main idea.

EXERCISE 2

Working individually or with a group, identify the topic sentences in the following paragraphs. If the topic sentence is implied, write the point the paragraph conveys.

-

Nothing can dampen the excited anticipation of camping more than a dark, rainy day. Even the most adventurous campers can lose some of their enthusiasm on the drive to the campsite if the skies are dreary and damp. After reaching their destination, campers must then "set up camp" in the downpour. This includes keeping the inside of the tent dry and free from mud, getting the sleeping bags situated dryly, and protecting food from the downpour. If the sleeping bags happen to get wet, the cold also becomes a major factor. A sleeping bag usually provides warmth on a camping trip; a wet sleeping bag provides none. Combining wind with rain can cause frigid temperatures, causing any outside activities to be delayed. Even inside the tent problems may arise due to heavy winds. More than a few campers have had their tents blown down because of the wind, which once again begins the frustrating task of "setting up camp" in the downpour. It is wise to check the weather forecast before embarking on camping trips; however, mother nature is often unpredictable and there is no guarantee bad weather will be eluded.

-

Another problem likely to be faced during a camping trip is run-ins with wildlife, which can range from mildly annoying to dangerous. Minor inconveniences include mosquitoes and ants. The swarming of mosquitoes can literally drive annoyed campers indoors. If an effective repellant is not used, the camper can spend an interminable night scratching, which will only worsen the itch. Ants do not usually attack campers, but keeping them out of the food can be quite an inconvenience. Extreme care must be taken not to leave food out before or after meals. If food is stored inside the tent, the tent must never be left open. In addition to swarming the food, ants inside a tent can crawl into sleeping bags and clothing. Although these insects cause minor discomfort, some wildlife encounters are potentially dangerous. There are many poisonous snakes in the United States, such as the water moccasin and the diamond-back rattlesnake. When hiking in the woods, the camper must be careful where he steps. Also, the tent must never be left open. Snakes, searching for either shade from the sun or shelter from the rain, can enter a tent. An encounter between an unwary camper and a surprised snake can prove to be fatal. Run-ins can range from unpleasant to dangerous, but the camper must realize that they are sometimes inevitable.

-

Perhaps the least serious camping troubles are equipment failures; these troubles often plague families camping for the first time. They arrive at the campsite at night and haphazardly set up their nine-person tent. They then settle down for a peaceful night's rest. Sometime during the night the family is awakened by a huge crash. The tent has fallen down. Sleepily, they awake and proceed to set up the tent in the rain. In the morning, everyone emerges from the tent, except for two. Their sleeping bag zippers have gotten caught. Finally, after fifteen minutes of struggling, they free themselves, only to realize another problem. Each family member's sleeping bag has been touching the sides of the tent. A tent is only waterproof if the sides are not touched. The sleeping bags and clothing are all drenched. Totally disillusioned with the "vacation," the frustrated family packs up immediately and drives home. Equipment failures may not seem very serious, but after campers encounter bad weather and annoying pests or wild animals, these failures can end any remaining hope for a peaceful vacation.

https://www.jscc.edu/academics/programs/writing-center/writing-resources/five-paragraph- essay.html

Body paragraphs in an essay come after the introductory paragraph. The sentences support the generalization in the topic sentence. If you need help in thinking of details, try using RENNS.

R = Reasons can provide support.

E = Examples can provide support.

N = Names can provide support.

N = Numbers can provide support.

S = Senses – sight, sound, smell, taste, touch – provide support.

The concluding paragraph of an essay needs to follow logically from your thesis statement and body paragraphs. Never merely tack on a conclusion. Your concluding paragraph provides a sense of completion, a finishing touch that enhances the whole essay.

-

Paragraph coherence

A paragraph has coherence when its sentences are connected in content and relate to each other in form and language. Coherence creates a smooth flow of thoughts within each paragraph as well as from one paragraph to another. Transitional words and expressions, deliberate repetition, and parallelism can help make your writing coherent.

Transitional expressions are words and phrases that express connections among ideas, both within and between paragraphs. Here are some tips for using transitions effectively.

-

Vary the transitional expressions that you use within a category.

-

Use each transitional expression precisely, according to its exact meaning.

|

ADDITION – also, besides, equally important, furthermore, in addition, moreover, too COMPARISON – in the same way, likewise, similarly CONCESSION – granted, naturally, of course CONTRAST – at the same time, certainly, despite the fact that, however, in contrast, instead, nevertheless, on the contrary, on the other hand, otherwise, still EMPHASIS – indeed, in fact, of course EXAMPLE – a case in point, as an illustration, for example, for instance, namely, specifically PLACE – here, in the background, in the front, nearby, there RESULT – accordingly, as a result, consequently, hence, then, therefore, thus SUMMARY – finally, in conclusion, in short, in summary TIME SEQUENCE – eventually, finally, meanwhile, next, now, once, then, today, tomorrow, subsequently, yesterday |

-

Academic writing from paragraph to essay. Dorothy E Zemach, Lisa A Rumisek. Macmillan , 2015

-

Quick access, reference for writers, 7th edition. Lynn Q. Troyka, Douglas Hesse. Pearson, 2013

шағым қалдыра аласыз